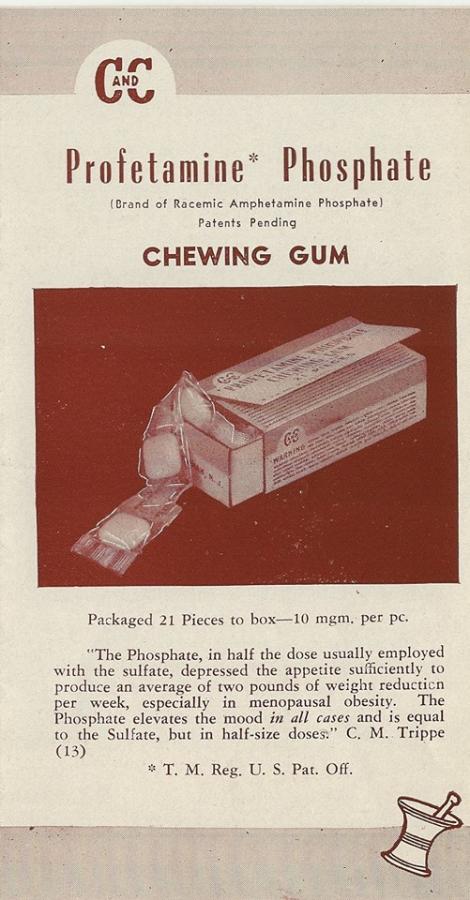

Clark & Clark Company Amphetamine Gum Brochure from the "Pill Factory"

Wenonah Fire Department photo of the Clark & Clark Manufacturing Pharmacy after the 1969 fire, used with permission of the archivist.

More photos from the 1969 Pill Factory Fire - https://www.jerseypix.com/FireFighting/The-WFC-Photo-Project-COMPLETE/Fi...

The 1971 Pill Factory Fire https://www.jerseypix.com/FireFighting/The-WFC-Photo-Project-COMPLETE/Fi...

The 1971 Pill Factory Fire https://www.jerseypix.com/FireFighting/The-WFC-Photo-Project-COMPLETE/Fi...

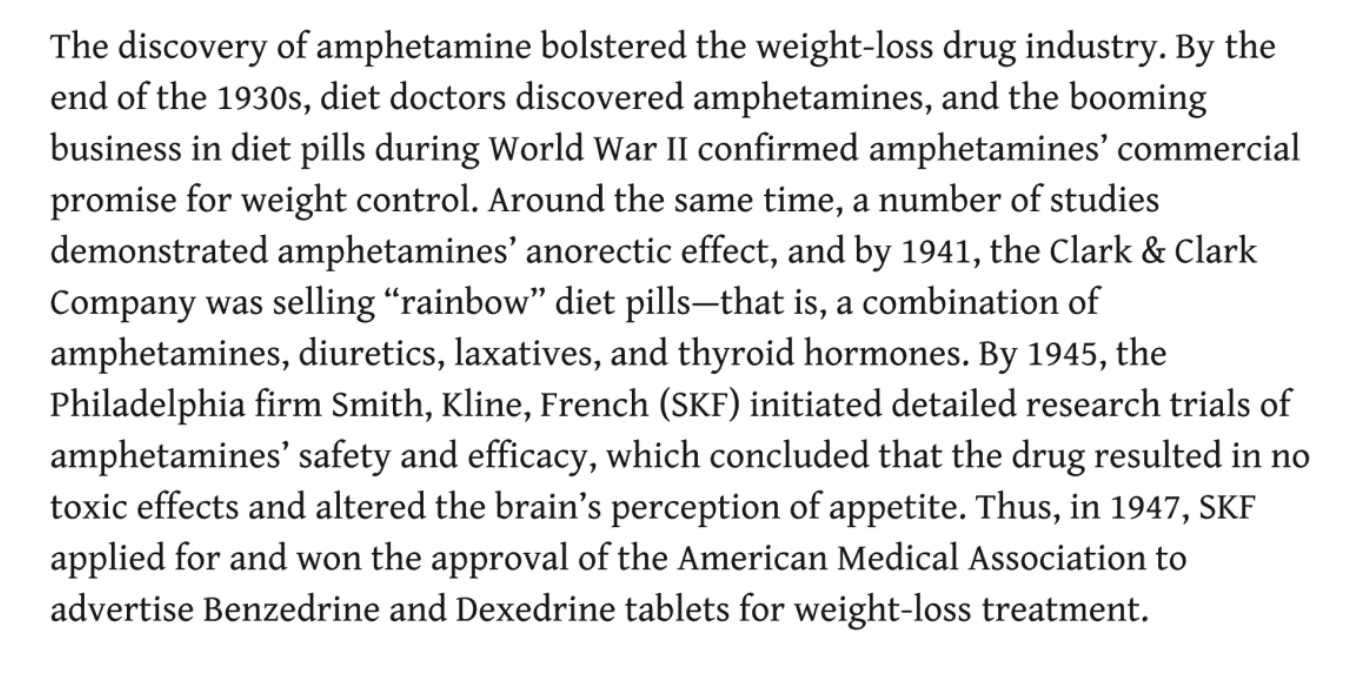

Amazing weight loss pills -- better than hosting beef tapeworms to lose weight. Above quote is from The SAGE Encyclopedia of Pharmacology and Society by Sarah E. Boslaugh

SAGE Publications, Sep 15, 2015 -.

Ever wonder what products were associated with "The Pill Factory" down along the railroad tracks on the south end of Wenonah? One of the patents awarded to Clark & Clark is linked below, too.

Investigators found that in October 1945 Clark & Clark were producing about 2 million Clarkotabs per day. See excerpt from the 2009 book "On Speed" in the list of links below.

Investigators found that in October 1945 Clark & Clark were producing about 2 million Clarkotabs per day. See excerpt from the 2009 book "On Speed" in the list of links below.

At least one US patent was awarded to Clark & Clark Company.

Check out this 1947 Profetamine Phosphate Brochure from Clark & Clark.

Click on photo of the box of gum below to see the whole brochure.

Click on photo of the box of gum below to see the whole brochure.

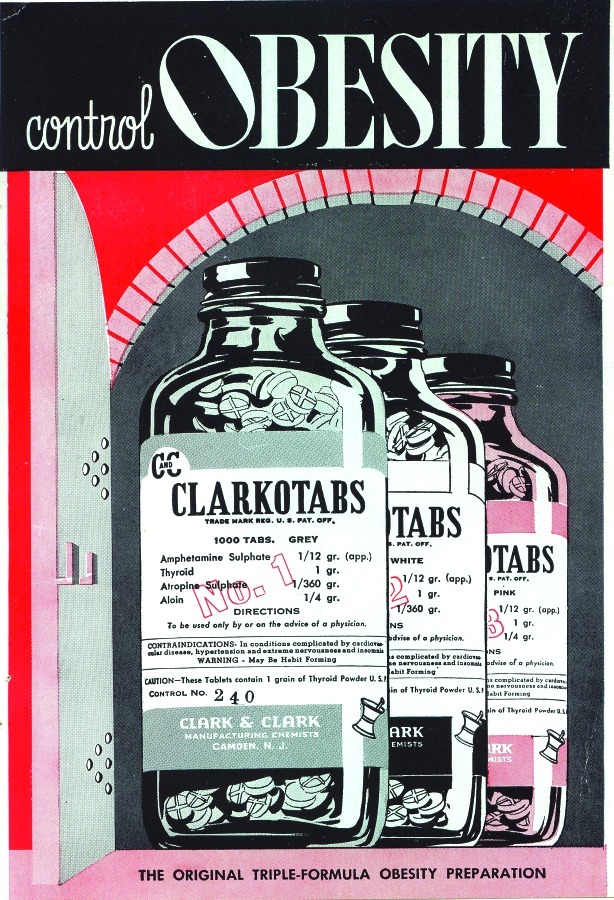

Another Clark & Clark product -- Clarkotabs, for obesity.

The discovery of amphetamine energized the weight loss industry. Introduced as the Benzedrine inhaler in 1932 by venerable Philadelphia firm Smith, Kline, and French, the American Medical Association (AMA) soon recognized Benzedrine as a treatment of narcolepsy, postencephaletic Parkinsonism, and certain depressive psychopathic conditions.9 Several clinical studies first published in the late 1930s demonstrated amphetamine's anorectic effect.10 The Clark & Clark Company of Camden, NJ, established in 1941, was one of the earliest manufacturers of diet pills combining amphetamine sulfate and thyroid along with phenobarbital, aloin, and atropine sulfate to counteract untoward effects.11 These diet pills, marketed as Clarkotabs, were among the first mass-produced rainbow pills (Figure 1).

The Pill Factory was accused of patent infringement -- drug wars of a sort --- right in Wenonah -- 1. “Supplementary Factory Inspection Report,” 5 March 1943, attached to O. Olsen to Chief, New York Station, 16 March 1943, AF 10-762 (Clark & Clark), vol. 1, Files, Food and Drug Administration, Suitland, MD. Clark & Clark reformulated its Clarkotabs with methamphetamine later in the decade upon being sued by Smith, Kline and French for patent infringement. See Rasmussen, “America's First Amphetamine Epidemic,” 975; and Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry, “Drugs for Obesity,” Journal of the American Medical Association 134 (1947): 527–529. Rasmussen, On Speed, 106 ff., discusses Smith, Kline and French's strategy to litigate amphetamine interlopers, such as Clark & Clark. [Ref list]

Selling the pills was done in certain unusual ways.

EXPANDING THE US MARKET FOR RAINBOW PILLS, 1940S TO 1970S

From 1940 to 1950, several other small firms formed for the same purpose, including Western Research Laboratories of Denver,12 the Lanpar Company of Dallas (1950), and Mills Pharmaceuticals of St Louis (1950). These firms were all novices to the business of pharmaceuticals, yet all committed to finding a foothold in a unique approach to weight loss, an approach that the larger and established companies appeared to avoid. These manufacturers did not have the standing with the medical profession that the traditional so-called ethical manufacturers enjoyed. For example, the Dallas County Medical Society and the Texas Medical Association would not accept advertising from a rainbow pill manufacturer that was located in its own backyard, nor would the societies allow the firms to exhibit at their meetings.13

A number of unusual marketing methods set the rainbow pill companies apart from most of the pharmaceutical industry. For example, there were the brightly colored tablets and capsules. Clark & Clark's Clarkotabs came in green, white, blue, pink, gray, and yellow tablets (Figure 1). Firms manufactured different formulations of their diet pills and many formulations came in a half dozen or more different colors. The use of colorful pills was not just aesthetic, but also an important part of the regimen, as a Lanpar brochure explained to prescribers:

You should have at least more than one color of every medication because [imagine] here come two women together. Do not give them the same color tablet. Don't let them go out and say, “Well, all you have got to do is get those blue pills.” Give one of them blue and one of them pink. After all, it is individual medication for that patient. That's a little psychology and is well worth it … it is particularly designed for them.14

Despite the fact that patients moved in and out of the office with little history-taking or evaluation of any form, the fanciful variety of rainbow pill colors was intended to avoid the perception of factory-line therapeutics. Instead, the rainbow colors suggested personalized attention, a treatment uniquely crafted for the patient's individual weight loss requirements; a clearly insidious version of what might otherwise be termed “personalized medicine” today. The patient typically would leave the office with several dozen tablets in a variety of colors.

Rainbow diet pill formulations varied over the years both within a firm's portfolio as well as between firms. Although there was no standard formulation, the pills usually contained a selection of d-amphetamine, chlorthalidone, and thyroid hormone as weight loss agents, and digitalis, barbiturates, potassium, glandular extracts, and belladonna were added to counter side effects (Table 1).15 Particularly troubling was the dosage of medicines a patient might receive. Some dosages were excessive and led to severe complications, such as the death of a 19-year-old who was prescribed a daily regimen of 650 milligrams desiccated thyroid, 50 milligrams digitalis leaf, 25 milligrams amphetamine, 50 milligrams chlorthalidone, and 500 milligrams potassium.16

Selling the pills was done in certain unusual ways.

EXPANDING THE US MARKET FOR RAINBOW PILLS, 1940S TO 1970S

From 1940 to 1950, several other small firms formed for the same purpose, including Western Research Laboratories of Denver,12 the Lanpar Company of Dallas (1950), and Mills Pharmaceuticals of St Louis (1950). These firms were all novices to the business of pharmaceuticals, yet all committed to finding a foothold in a unique approach to weight loss, an approach that the larger and established companies appeared to avoid. These manufacturers did not have the standing with the medical profession that the traditional so-called ethical manufacturers enjoyed. For example, the Dallas County Medical Society and the Texas Medical Association would not accept advertising from a rainbow pill manufacturer that was located in its own backyard, nor would the societies allow the firms to exhibit at their meetings.13

A number of unusual marketing methods set the rainbow pill companies apart from most of the pharmaceutical industry. For example, there were the brightly colored tablets and capsules. Clark & Clark's Clarkotabs came in green, white, blue, pink, gray, and yellow tablets (Figure 1). Firms manufactured different formulations of their diet pills and many formulations came in a half dozen or more different colors. The use of colorful pills was not just aesthetic, but also an important part of the regimen, as a Lanpar brochure explained to prescribers:

You should have at least more than one color of every medication because [imagine] here come two women together. Do not give them the same color tablet. Don't let them go out and say, “Well, all you have got to do is get those blue pills.” Give one of them blue and one of them pink. After all, it is individual medication for that patient. That's a little psychology and is well worth it … it is particularly designed for them.14

Despite the fact that patients moved in and out of the office with little history-taking or evaluation of any form, the fanciful variety of rainbow pill colors was intended to avoid the perception of factory-line therapeutics. Instead, the rainbow colors suggested personalized attention, a treatment uniquely crafted for the patient's individual weight loss requirements; a clearly insidious version of what might otherwise be termed “personalized medicine” today. The patient typically would leave the office with several dozen tablets in a variety of colors.

Rainbow diet pill formulations varied over the years both within a firm's portfolio as well as between firms. Although there was no standard formulation, the pills usually contained a selection of d-amphetamine, chlorthalidone, and thyroid hormone as weight loss agents, and digitalis, barbiturates, potassium, glandular extracts, and belladonna were added to counter side effects (Table 1).15 Particularly troubling was the dosage of medicines a patient might receive. Some dosages were excessive and led to severe complications, such as the death of a 19-year-old who was prescribed a daily regimen of 650 milligrams desiccated thyroid, 50 milligrams digitalis leaf, 25 milligrams amphetamine, 50 milligrams chlorthalidone, and 500 milligrams potassium.16

From 1940 to 1950, several other small firms formed for the same purpose, including Western Research Laboratories of Denver,12 the Lanpar Company of Dallas (1950), and Mills Pharmaceuticals of St Louis (1950). These firms were all novices to the business of pharmaceuticals, yet all committed to finding a foothold in a unique approach to weight loss, an approach that the larger and established companies appeared to avoid. These manufacturers did not have the standing with the medical profession that the traditional so-called ethical manufacturers enjoyed. For example, the Dallas County Medical Society and the Texas Medical Association would not accept advertising from a rainbow pill manufacturer that was located in its own backyard, nor would the societies allow the firms to exhibit at their meetings.13

A number of unusual marketing methods set the rainbow pill companies apart from most of the pharmaceutical industry. For example, there were the brightly colored tablets and capsules. Clark & Clark's Clarkotabs came in green, white, blue, pink, gray, and yellow tablets (Figure 1). Firms manufactured different formulations of their diet pills and many formulations came in a half dozen or more different colors. The use of colorful pills was not just aesthetic, but also an important part of the regimen, as a Lanpar brochure explained to prescribers:

You should have at least more than one color of every medication because [imagine] here come two women together. Do not give them the same color tablet. Don't let them go out and say, “Well, all you have got to do is get those blue pills.” Give one of them blue and one of them pink. After all, it is individual medication for that patient. That's a little psychology and is well worth it … it is particularly designed for them.14

Despite the fact that patients moved in and out of the office with little history-taking or evaluation of any form, the fanciful variety of rainbow pill colors was intended to avoid the perception of factory-line therapeutics. Instead, the rainbow colors suggested personalized attention, a treatment uniquely crafted for the patient's individual weight loss requirements; a clearly insidious version of what might otherwise be termed “personalized medicine” today. The patient typically would leave the office with several dozen tablets in a variety of colors.

Rainbow diet pill formulations varied over the years both within a firm's portfolio as well as between firms. Although there was no standard formulation, the pills usually contained a selection of d-amphetamine, chlorthalidone, and thyroid hormone as weight loss agents, and digitalis, barbiturates, potassium, glandular extracts, and belladonna were added to counter side effects (Table 1).15 Particularly troubling was the dosage of medicines a patient might receive. Some dosages were excessive and led to severe complications, such as the death of a 19-year-old who was prescribed a daily regimen of 650 milligrams desiccated thyroid, 50 milligrams digitalis leaf, 25 milligrams amphetamine, 50 milligrams chlorthalidone, and 500 milligrams potassium.16

Despite the fact that patients moved in and out of the office with little history-taking or evaluation of any form, the fanciful variety of rainbow pill colors was intended to avoid the perception of factory-line therapeutics. Instead, the rainbow colors suggested personalized attention, a treatment uniquely crafted for the patient's individual weight loss requirements; a clearly insidious version of what might otherwise be termed “personalized medicine” today. The patient typically would leave the office with several dozen tablets in a variety of colors.

Rainbow diet pill formulations varied over the years both within a firm's portfolio as well as between firms. Although there was no standard formulation, the pills usually contained a selection of d-amphetamine, chlorthalidone, and thyroid hormone as weight loss agents, and digitalis, barbiturates, potassium, glandular extracts, and belladonna were added to counter side effects (Table 1).15 Particularly troubling was the dosage of medicines a patient might receive. Some dosages were excessive and led to severe complications, such as the death of a 19-year-old who was prescribed a daily regimen of 650 milligrams desiccated thyroid, 50 milligrams digitalis leaf, 25 milligrams amphetamine, 50 milligrams chlorthalidone, and 500 milligrams potassium.16

TABLE 1—

Common Ingredients of Rainbow Diet Pills, 1940s–Present

Typical Ingredients to Induce Weight Loss Typical Ingredients to Mask Side Effects Regulatory Response

United States, 1940s–1960s

d-amphetamine....................................cardiac glycosides...............FDA interdiction and court-ordered injunctions 1968

diuretics........................................barbiturates

thyroid hormones.................................corticosteroids

laxatives........................................potassium

phenolphthalein..................................belladonna

herbal ingredients...............................glandular extracts

Spain, 1980s–presenta

amphetamine derivatives..........................benzodiazepines...................Spanish regulatory ban 1997

fenproporex......................................corticosteroids

diethylpropion...................................glandular extracts

fenfluramine

thyroid hormones

diuretics

laxatives

herbal ingredients

Brazil, 1980s–present

amphetamine derivatives..........................selective serotonin..............Brazilian regulatory ban 2007

fenproporex......................................uptake inhibitors

diethylpropion...................................benzodiazepines

laxatives

diuretics

United States, 1980s–present

sibutramine......................................selective serotonin..............FDA alerts 1987–present

fenproporex......................................uptake inhibitors

ephedrine........................................benzodiazepines

thyroid hormones.................................beta-blockers

laxatives

phenolphthalein

herbal ingredients

Note. FDA = US Food and Drug Administration.

In Spain and Brazil, rainbow pills are often referred to as compounded diet pills (fórmulas magistrales para la obesidad [Spanish] and remédio de emagrecer manipulado [Portuguese]) among other names.

The rainbow pill firms sold their products directly to physicians. This uncommon, although not unprecedented arrangement, involved physicians selling the pills directly to patients, often in large quantities, and left pharmacies out of the rainbow pill pipeline. The prescriber would charge from $5 to $40 for brief visits. Physicians specializing in rainbow pill practices could see an impressive number of patients. “On a slow day” one physician was able to see more than 100 patients.17 Companies also assisted physicians in setting up obesity practices and troubleshooting business problems. The rainbow firms reminded their clients that the endgame was to create a weight practice that would allow the physician more leisure time, plus “it is a very nice practice to handle if you ever become physically incapacitated to any more or less extent.”18

Even more novel were some of the measures the companies pursued to “educate” potential clients about the rainbow pills. All-expense-paid pharmaceutical symposia ostensibly educated physicians about the therapeutics of obesity. However, in contrast to the teaching of contemporary medical textbooks,19 physicians at these symposia learned that weight gain was not a function of one's eating or exercising.20 The symposia faculty taught that endocrinologic imbalances led to obesity, and their regimens were rational because overweight patients often suffered from heart failure, low estrogen states, and hypothyroidism. By promoting an all-out endogenous etiology of obesity, the firms justified a wide range of pharmaceutical ingredients.21

By contrast, standard texts of the era emphasized that the first step in treating obesity should be proper diet and exercise. Although they recognized that thyroid hormone would accelerate metabolism, contemporary texts recommended it only when hypothyroidism was documented. In fact, several contemporary sources described a range of serious symptoms, including thyrotoxicosis, when thyroid hormone was used routinely for weight loss. Amphetamines were understood to control appetite, but shortly after their discovery academic physicians also recognized the dangers of long-term cardiac stimulation and other problems.22 Researchers early in this period acknowledged the potential for habituation, but revelation of their addictive properties took a little longer to be included in some texts. Medical textbooks cited amphetamines as, at best, temporary expedients to facilitate restricted eating habits. As for the role of digitalis in weight management, one author remarked that it was “a drastic step to take, for digitalis is very potent.” Some contemporary sources occasionally recommended diuretics in weight control.23

The theoretical foundation of the rainbow pill practice distinctly opposed what physicians would have learned in school and in continuing education about treating obesity.24 Furthermore, the pharmaceutical firms marketing these pills enjoyed little, if any, respect among academic physicians.25 Despite these barriers, the firms were able to attract many physicians to rainbow pill practices. By 1967, 5000 MDs and DOs devoted a majority of their practices to weight loss. Of these, 2000 practices focused exclusively on weight reduction. According to a Congressional investigation that year, weight loss clinics earned $250 million annually just in patient fees, and it was estimated that patients spent an additional $120 million on rainbow pills.26

A rainbow pill clinic could be both profitable and relatively easy to operate compared with other general medical practices, even if it flew in the face of professional standards and ethics. As the practice increased, so did concerns about attendant health risks. The AMA characterized these drugs as having no rational therapeutic use, and therefore [their] administration for treatment of obesity must be regarded as misuse… . It now remains for organized medicine, through its local societies, to see that these abuses are not being perpetrated by members of the medical profession.27

Although patients were often reluctant to disclose use of rainbow pills to their regular physicians, adverse events, including deaths, began to be reported to the FDA as early as the 1940s. In the early 1950s, additional adverse reactions including deaths prompted a detailed investigation by the agency.28 However, the FDA dithered over whether to intervene, concerned about both the adequacy of the evidence and interfering with physicians’ practice of medicine.

To be sure, there was a striking difference of opinion within the agency regarding whether to take decisive action against the rainbow pills.29 By contrast, FDA dealt quite differently with another diet drug in the 1930s, dinitrophenol. Abandoned by clinicians early in that decade because of a number of severe side effects, several firms introduced about two dozen preparations for self-medication, which was still technically legal under the law at that time. The FDA latched on to therapeutic claims in testimonials to generate misbranding charges against at least one firm, which proved effective in removing at least some products from interstate commerce. In that case, the agency head determined the interests of the public health were worth the risks of taking a regulatory leap to move against a dangerous drug like dinitrophenol in the years that preceded the enhanced powers offered by the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.30

The FDA continued to monitor the rainbow pill manufacturers. For example, officials in the bureaus of Medicine and Regulatory Compliance met in 1964 to address the problem of regulating thyroid and digitalis used in weight loss. Theoretically, the companies could claim these two drugs could be grandfathered in under the 1938 law, because both had been on the market long before. Mass seizures of the product would be logistically difficult because the rainbow pills were sold to physicians via mail order and, thus, a seizure would have to be made at thousands of the practitioner's offices. Officials with the FDA also considered requiring that the rainbow pill manufacturers provide full disclosure information, but the firms could very well agree to do that, which “might very well defeat the purpose of the seizures; said purpose being to cease the distribution of such irrational products.” Finally, agency officials considered bringing health hazard charges against the rainbow pills, but understood that any expert testimony would be opposed equally by testimonials of satisfied users and prescribing practitioners who would claim that the products were safe and effective. Instead, the FDA decided to continue to collect evidence of animal toxicity and patient injuries.31

Two important events outside of the FDA changed the regulatory landscape in 1968. A slim investigative reporter for Life magazine reported on her experiences posing as a patient at 10 obesity clinics (Figure 2). Despite receiving only perfunctory evaluations and sometimes counseled that she did not need to lose weight, she was prescribed more than 1500 pills.32 That same month, the US Senate, following months of detailed investigations in which the Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly identified at least 60 deaths and many more serious adverse effects (Figure 3), launched hearings into the rainbow diet pill industry.33

Paragraphs above come from link below

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3482033/

Smithsonian Magazine article from 2017

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/speedy-history-americas-addiction...

Booth at convention

https://archive.org/details/journalofmedical52unse_0/page/180

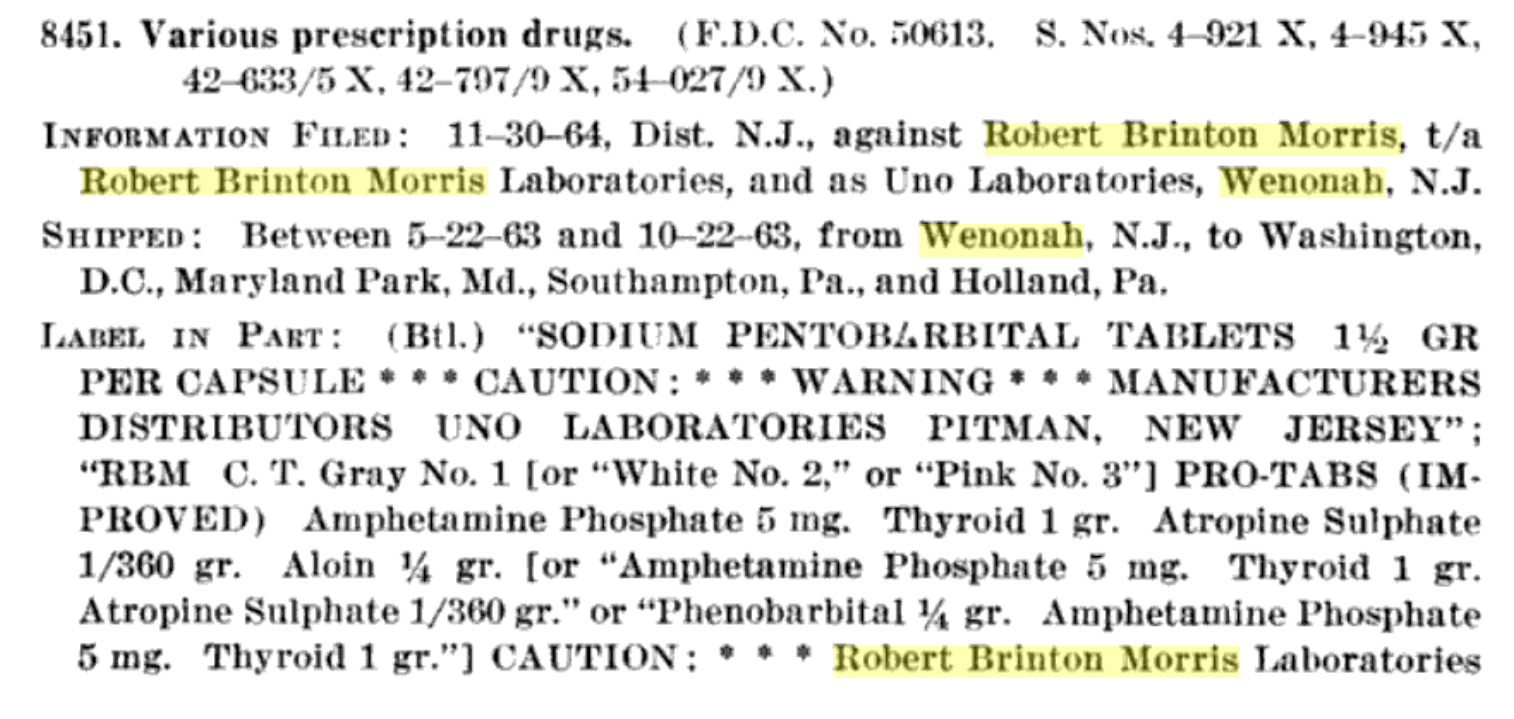

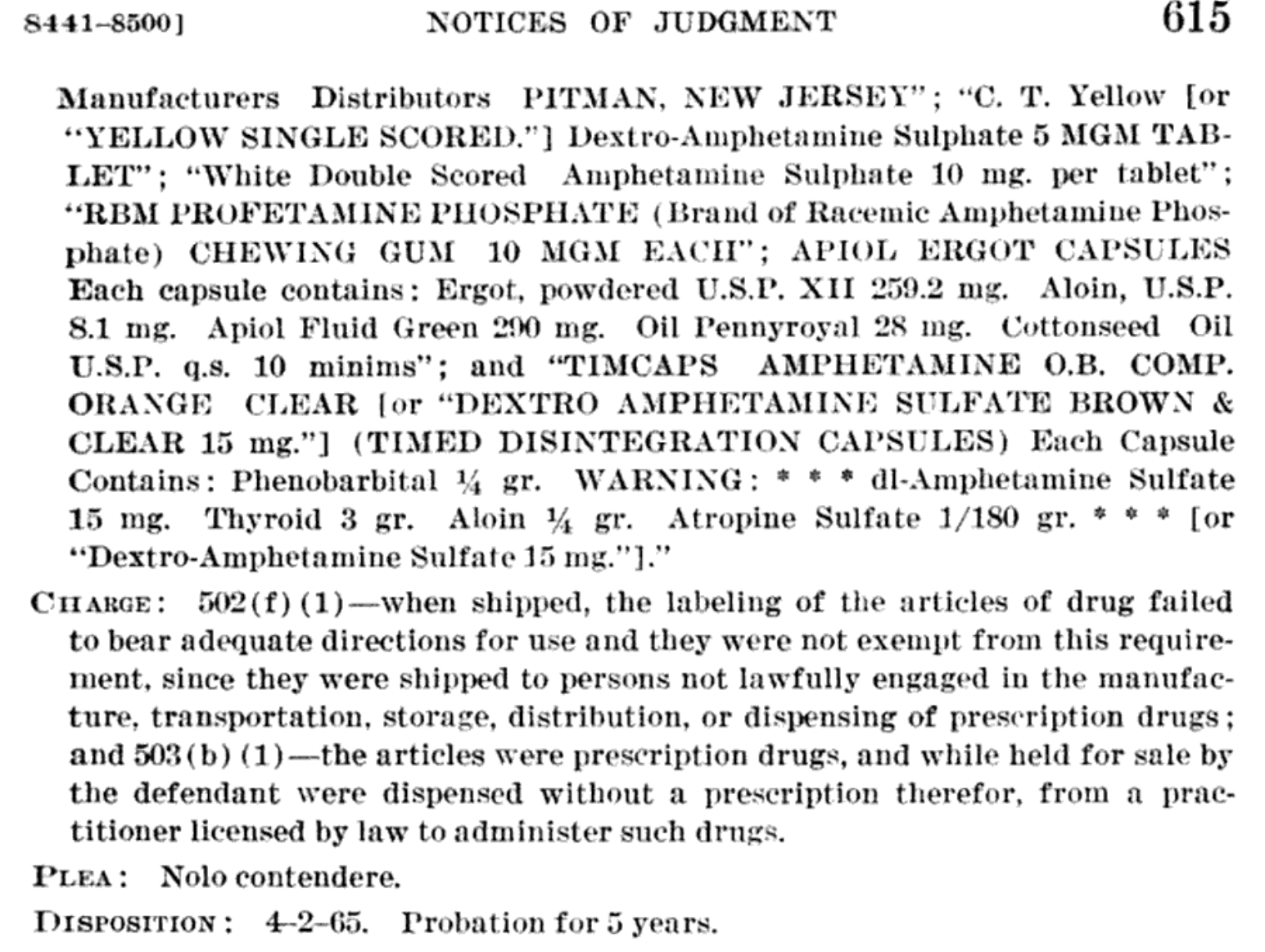

After a while the long arm of the law reached out to Clark & Clark. 5 years probabtion for Robert Brinton Morris, Sr.

In 1951 there was a judgement against Robert Brinton Morris.

https://fdanj.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/ddnj03392

Even more novel were some of the measures the companies pursued to “educate” potential clients about the rainbow pills. All-expense-paid pharmaceutical symposia ostensibly educated physicians about the therapeutics of obesity. However, in contrast to the teaching of contemporary medical textbooks,19 physicians at these symposia learned that weight gain was not a function of one's eating or exercising.20 The symposia faculty taught that endocrinologic imbalances led to obesity, and their regimens were rational because overweight patients often suffered from heart failure, low estrogen states, and hypothyroidism. By promoting an all-out endogenous etiology of obesity, the firms justified a wide range of pharmaceutical ingredients.21

By contrast, standard texts of the era emphasized that the first step in treating obesity should be proper diet and exercise. Although they recognized that thyroid hormone would accelerate metabolism, contemporary texts recommended it only when hypothyroidism was documented. In fact, several contemporary sources described a range of serious symptoms, including thyrotoxicosis, when thyroid hormone was used routinely for weight loss. Amphetamines were understood to control appetite, but shortly after their discovery academic physicians also recognized the dangers of long-term cardiac stimulation and other problems.22 Researchers early in this period acknowledged the potential for habituation, but revelation of their addictive properties took a little longer to be included in some texts. Medical textbooks cited amphetamines as, at best, temporary expedients to facilitate restricted eating habits. As for the role of digitalis in weight management, one author remarked that it was “a drastic step to take, for digitalis is very potent.” Some contemporary sources occasionally recommended diuretics in weight control.23

The theoretical foundation of the rainbow pill practice distinctly opposed what physicians would have learned in school and in continuing education about treating obesity.24 Furthermore, the pharmaceutical firms marketing these pills enjoyed little, if any, respect among academic physicians.25 Despite these barriers, the firms were able to attract many physicians to rainbow pill practices. By 1967, 5000 MDs and DOs devoted a majority of their practices to weight loss. Of these, 2000 practices focused exclusively on weight reduction. According to a Congressional investigation that year, weight loss clinics earned $250 million annually just in patient fees, and it was estimated that patients spent an additional $120 million on rainbow pills.26

A rainbow pill clinic could be both profitable and relatively easy to operate compared with other general medical practices, even if it flew in the face of professional standards and ethics. As the practice increased, so did concerns about attendant health risks. The AMA characterized these drugs as having no rational therapeutic use, and therefore [their] administration for treatment of obesity must be regarded as misuse… . It now remains for organized medicine, through its local societies, to see that these abuses are not being perpetrated by members of the medical profession.27

Although patients were often reluctant to disclose use of rainbow pills to their regular physicians, adverse events, including deaths, began to be reported to the FDA as early as the 1940s. In the early 1950s, additional adverse reactions including deaths prompted a detailed investigation by the agency.28 However, the FDA dithered over whether to intervene, concerned about both the adequacy of the evidence and interfering with physicians’ practice of medicine.

To be sure, there was a striking difference of opinion within the agency regarding whether to take decisive action against the rainbow pills.29 By contrast, FDA dealt quite differently with another diet drug in the 1930s, dinitrophenol. Abandoned by clinicians early in that decade because of a number of severe side effects, several firms introduced about two dozen preparations for self-medication, which was still technically legal under the law at that time. The FDA latched on to therapeutic claims in testimonials to generate misbranding charges against at least one firm, which proved effective in removing at least some products from interstate commerce. In that case, the agency head determined the interests of the public health were worth the risks of taking a regulatory leap to move against a dangerous drug like dinitrophenol in the years that preceded the enhanced powers offered by the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.30

The FDA continued to monitor the rainbow pill manufacturers. For example, officials in the bureaus of Medicine and Regulatory Compliance met in 1964 to address the problem of regulating thyroid and digitalis used in weight loss. Theoretically, the companies could claim these two drugs could be grandfathered in under the 1938 law, because both had been on the market long before. Mass seizures of the product would be logistically difficult because the rainbow pills were sold to physicians via mail order and, thus, a seizure would have to be made at thousands of the practitioner's offices. Officials with the FDA also considered requiring that the rainbow pill manufacturers provide full disclosure information, but the firms could very well agree to do that, which “might very well defeat the purpose of the seizures; said purpose being to cease the distribution of such irrational products.” Finally, agency officials considered bringing health hazard charges against the rainbow pills, but understood that any expert testimony would be opposed equally by testimonials of satisfied users and prescribing practitioners who would claim that the products were safe and effective. Instead, the FDA decided to continue to collect evidence of animal toxicity and patient injuries.31

Two important events outside of the FDA changed the regulatory landscape in 1968. A slim investigative reporter for Life magazine reported on her experiences posing as a patient at 10 obesity clinics (Figure 2). Despite receiving only perfunctory evaluations and sometimes counseled that she did not need to lose weight, she was prescribed more than 1500 pills.32 That same month, the US Senate, following months of detailed investigations in which the Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly identified at least 60 deaths and many more serious adverse effects (Figure 3), launched hearings into the rainbow diet pill industry.33

Paragraphs above come from link below

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3482033/

Smithsonian Magazine article from 2017

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/speedy-history-americas-addiction...

Booth at convention

https://archive.org/details/journalofmedical52unse_0/page/180

After a while the long arm of the law reached out to Clark & Clark. 5 years probabtion for Robert Brinton Morris, Sr.

In 1951 there was a judgement against Robert Brinton Morris.

https://fdanj.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/ddnj03392

The theoretical foundation of the rainbow pill practice distinctly opposed what physicians would have learned in school and in continuing education about treating obesity.24 Furthermore, the pharmaceutical firms marketing these pills enjoyed little, if any, respect among academic physicians.25 Despite these barriers, the firms were able to attract many physicians to rainbow pill practices. By 1967, 5000 MDs and DOs devoted a majority of their practices to weight loss. Of these, 2000 practices focused exclusively on weight reduction. According to a Congressional investigation that year, weight loss clinics earned $250 million annually just in patient fees, and it was estimated that patients spent an additional $120 million on rainbow pills.26

A rainbow pill clinic could be both profitable and relatively easy to operate compared with other general medical practices, even if it flew in the face of professional standards and ethics. As the practice increased, so did concerns about attendant health risks. The AMA characterized these drugs as having no rational therapeutic use, and therefore [their] administration for treatment of obesity must be regarded as misuse… . It now remains for organized medicine, through its local societies, to see that these abuses are not being perpetrated by members of the medical profession.27

Although patients were often reluctant to disclose use of rainbow pills to their regular physicians, adverse events, including deaths, began to be reported to the FDA as early as the 1940s. In the early 1950s, additional adverse reactions including deaths prompted a detailed investigation by the agency.28 However, the FDA dithered over whether to intervene, concerned about both the adequacy of the evidence and interfering with physicians’ practice of medicine.

To be sure, there was a striking difference of opinion within the agency regarding whether to take decisive action against the rainbow pills.29 By contrast, FDA dealt quite differently with another diet drug in the 1930s, dinitrophenol. Abandoned by clinicians early in that decade because of a number of severe side effects, several firms introduced about two dozen preparations for self-medication, which was still technically legal under the law at that time. The FDA latched on to therapeutic claims in testimonials to generate misbranding charges against at least one firm, which proved effective in removing at least some products from interstate commerce. In that case, the agency head determined the interests of the public health were worth the risks of taking a regulatory leap to move against a dangerous drug like dinitrophenol in the years that preceded the enhanced powers offered by the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.30

The FDA continued to monitor the rainbow pill manufacturers. For example, officials in the bureaus of Medicine and Regulatory Compliance met in 1964 to address the problem of regulating thyroid and digitalis used in weight loss. Theoretically, the companies could claim these two drugs could be grandfathered in under the 1938 law, because both had been on the market long before. Mass seizures of the product would be logistically difficult because the rainbow pills were sold to physicians via mail order and, thus, a seizure would have to be made at thousands of the practitioner's offices. Officials with the FDA also considered requiring that the rainbow pill manufacturers provide full disclosure information, but the firms could very well agree to do that, which “might very well defeat the purpose of the seizures; said purpose being to cease the distribution of such irrational products.” Finally, agency officials considered bringing health hazard charges against the rainbow pills, but understood that any expert testimony would be opposed equally by testimonials of satisfied users and prescribing practitioners who would claim that the products were safe and effective. Instead, the FDA decided to continue to collect evidence of animal toxicity and patient injuries.31

Two important events outside of the FDA changed the regulatory landscape in 1968. A slim investigative reporter for Life magazine reported on her experiences posing as a patient at 10 obesity clinics (Figure 2). Despite receiving only perfunctory evaluations and sometimes counseled that she did not need to lose weight, she was prescribed more than 1500 pills.32 That same month, the US Senate, following months of detailed investigations in which the Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly identified at least 60 deaths and many more serious adverse effects (Figure 3), launched hearings into the rainbow diet pill industry.33

Paragraphs above come from link below

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3482033/

Smithsonian Magazine article from 2017

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/speedy-history-americas-addiction...

Booth at convention

https://archive.org/details/journalofmedical52unse_0/page/180

After a while the long arm of the law reached out to Clark & Clark. 5 years probabtion for Robert Brinton Morris, Sr.

In 1951 there was a judgement against Robert Brinton Morris.

https://fdanj.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/ddnj03392

Although patients were often reluctant to disclose use of rainbow pills to their regular physicians, adverse events, including deaths, began to be reported to the FDA as early as the 1940s. In the early 1950s, additional adverse reactions including deaths prompted a detailed investigation by the agency.28 However, the FDA dithered over whether to intervene, concerned about both the adequacy of the evidence and interfering with physicians’ practice of medicine.

To be sure, there was a striking difference of opinion within the agency regarding whether to take decisive action against the rainbow pills.29 By contrast, FDA dealt quite differently with another diet drug in the 1930s, dinitrophenol. Abandoned by clinicians early in that decade because of a number of severe side effects, several firms introduced about two dozen preparations for self-medication, which was still technically legal under the law at that time. The FDA latched on to therapeutic claims in testimonials to generate misbranding charges against at least one firm, which proved effective in removing at least some products from interstate commerce. In that case, the agency head determined the interests of the public health were worth the risks of taking a regulatory leap to move against a dangerous drug like dinitrophenol in the years that preceded the enhanced powers offered by the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.30

The FDA continued to monitor the rainbow pill manufacturers. For example, officials in the bureaus of Medicine and Regulatory Compliance met in 1964 to address the problem of regulating thyroid and digitalis used in weight loss. Theoretically, the companies could claim these two drugs could be grandfathered in under the 1938 law, because both had been on the market long before. Mass seizures of the product would be logistically difficult because the rainbow pills were sold to physicians via mail order and, thus, a seizure would have to be made at thousands of the practitioner's offices. Officials with the FDA also considered requiring that the rainbow pill manufacturers provide full disclosure information, but the firms could very well agree to do that, which “might very well defeat the purpose of the seizures; said purpose being to cease the distribution of such irrational products.” Finally, agency officials considered bringing health hazard charges against the rainbow pills, but understood that any expert testimony would be opposed equally by testimonials of satisfied users and prescribing practitioners who would claim that the products were safe and effective. Instead, the FDA decided to continue to collect evidence of animal toxicity and patient injuries.31

Two important events outside of the FDA changed the regulatory landscape in 1968. A slim investigative reporter for Life magazine reported on her experiences posing as a patient at 10 obesity clinics (Figure 2). Despite receiving only perfunctory evaluations and sometimes counseled that she did not need to lose weight, she was prescribed more than 1500 pills.32 That same month, the US Senate, following months of detailed investigations in which the Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly identified at least 60 deaths and many more serious adverse effects (Figure 3), launched hearings into the rainbow diet pill industry.33

Paragraphs above come from link below

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3482033/

Smithsonian Magazine article from 2017

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/speedy-history-americas-addiction...

Booth at convention

https://archive.org/details/journalofmedical52unse_0/page/180

After a while the long arm of the law reached out to Clark & Clark. 5 years probabtion for Robert Brinton Morris, Sr.

In 1951 there was a judgement against Robert Brinton Morris.

https://fdanj.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/ddnj03392

The FDA continued to monitor the rainbow pill manufacturers. For example, officials in the bureaus of Medicine and Regulatory Compliance met in 1964 to address the problem of regulating thyroid and digitalis used in weight loss. Theoretically, the companies could claim these two drugs could be grandfathered in under the 1938 law, because both had been on the market long before. Mass seizures of the product would be logistically difficult because the rainbow pills were sold to physicians via mail order and, thus, a seizure would have to be made at thousands of the practitioner's offices. Officials with the FDA also considered requiring that the rainbow pill manufacturers provide full disclosure information, but the firms could very well agree to do that, which “might very well defeat the purpose of the seizures; said purpose being to cease the distribution of such irrational products.” Finally, agency officials considered bringing health hazard charges against the rainbow pills, but understood that any expert testimony would be opposed equally by testimonials of satisfied users and prescribing practitioners who would claim that the products were safe and effective. Instead, the FDA decided to continue to collect evidence of animal toxicity and patient injuries.31

Two important events outside of the FDA changed the regulatory landscape in 1968. A slim investigative reporter for Life magazine reported on her experiences posing as a patient at 10 obesity clinics (Figure 2). Despite receiving only perfunctory evaluations and sometimes counseled that she did not need to lose weight, she was prescribed more than 1500 pills.32 That same month, the US Senate, following months of detailed investigations in which the Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly identified at least 60 deaths and many more serious adverse effects (Figure 3), launched hearings into the rainbow diet pill industry.33

Paragraphs above come from link below

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3482033/

Smithsonian Magazine article from 2017

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/speedy-history-americas-addiction...

Booth at convention

https://archive.org/details/journalofmedical52unse_0/page/180

After a while the long arm of the law reached out to Clark & Clark. 5 years probabtion for Robert Brinton Morris, Sr.

In 1951 there was a judgement against Robert Brinton Morris.

https://fdanj.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/ddnj03392

Paragraphs above come from link below

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3482033/

Smithsonian Magazine article from 2017

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/speedy-history-americas-addiction...

Booth at convention

https://archive.org/details/journalofmedical52unse_0/page/180

After a while the long arm of the law reached out to Clark & Clark. 5 years probabtion for Robert Brinton Morris, Sr.

In 1951 there was a judgement against Robert Brinton Morris.

https://fdanj.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/ddnj03392

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/speedy-history-americas-addiction...

Booth at convention

https://archive.org/details/journalofmedical52unse_0/page/180

After a while the long arm of the law reached out to Clark & Clark. 5 years probabtion for Robert Brinton Morris, Sr.

In 1951 there was a judgement against Robert Brinton Morris.

https://fdanj.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/ddnj03392

In 1951 there was a judgement against Robert Brinton Morris.

https://fdanj.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/ddnj03392